Historia Occulta

The past was hidden. The present is masked. The future? Just another beginning.

Welcome to the deeper story.

Powered by Tartaria Britannica.

Welcome to the deeper story.

Powered by Tartaria Britannica.

TGlist rating

0

0

TypePublic

Verification

Not verifiedTrust

Not trustedLocation

LanguageOther

Channel creation dateNov 19, 2024

Added to TGlist

Mar 28, 2025Linked chat

Latest posts in group "Historia Occulta"

19.05.202511:00

Notes Left in the Margin of the Flax Registers

By the 16th century, hemp wasn’t an alternative—it was infrastructure. Its fibers formed the rigging, sails, and caulking that kept imperial fleets afloat. Venice, Amsterdam, and London all relied on it, not just as a raw material but as a strategic asset. Nations passed laws mandating its cultivation. In Elizabethan England, landowners were required to sow hemp or face penalties. Without it, there would have been no naval dominance, no reliable canvas, no global expansion.

Its deeper roots stretch into ritual and subsistence. In ancient China, hemp was used for paper, textiles, and food as early as the Neolithic era. In Vedic India, bhang was consumed in devotional rites to Shiva. Herodotus describes Scythians using hemp smoke in burial ceremonies to induce altered states. Across Eurasia, it served both sacred and practical needs—a staple crop entwined with cosmology, trade, and medicine, not a fringe anomaly.

What changed was not the plant, but the politics around it. In the 20th century, hemp became collateral in regulatory campaigns against cannabis, with the 1937 Marihuana Tax Act in the U.S. effectively outlawing one of agriculture’s most versatile crops. It coincided, not incidentally, with the rise of synthetic fibers like nylon. What had been common knowledge—that hemp supported economies, industries, and ecologies—was quietly erased from public memory.

Follow @historiaocculta

By the 16th century, hemp wasn’t an alternative—it was infrastructure. Its fibers formed the rigging, sails, and caulking that kept imperial fleets afloat. Venice, Amsterdam, and London all relied on it, not just as a raw material but as a strategic asset. Nations passed laws mandating its cultivation. In Elizabethan England, landowners were required to sow hemp or face penalties. Without it, there would have been no naval dominance, no reliable canvas, no global expansion.

Its deeper roots stretch into ritual and subsistence. In ancient China, hemp was used for paper, textiles, and food as early as the Neolithic era. In Vedic India, bhang was consumed in devotional rites to Shiva. Herodotus describes Scythians using hemp smoke in burial ceremonies to induce altered states. Across Eurasia, it served both sacred and practical needs—a staple crop entwined with cosmology, trade, and medicine, not a fringe anomaly.

What changed was not the plant, but the politics around it. In the 20th century, hemp became collateral in regulatory campaigns against cannabis, with the 1937 Marihuana Tax Act in the U.S. effectively outlawing one of agriculture’s most versatile crops. It coincided, not incidentally, with the rise of synthetic fibers like nylon. What had been common knowledge—that hemp supported economies, industries, and ecologies—was quietly erased from public memory.

Follow @historiaocculta

18.05.202511:04

The Tower Still Stands

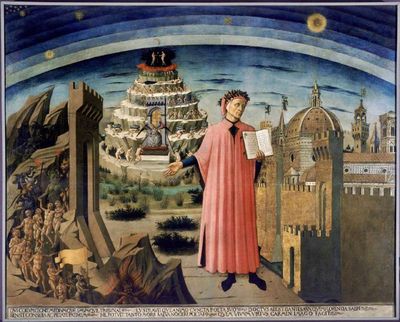

In Domenico di Michelino’s La Commedia illumina Firenze (1465), Dante is placed not in abstraction but in continuity—with Florence at his back and the full architecture of the afterlife before him. The Mount of Purgatory rises in tiers, but each level is active, not symbolic. At the base, a man is knighted by an angel—chosen through action, not birth. The ascent begins in struggle, shifts to urgency, and ends at a gate. Beyond it: Eden, not Heaven. A crowned man and woman wait in a walled garden.

To the left, another path breaks away. Here, figures lounge in comfort, but it doesn’t last. They are seized and pulled downward, funneled into Hell’s crowded tower. This descent is effortless—no climbing, no striving, only surrender. The structure is orderly. Each tier is populated. These aren’t loose ideas. They’re mapped destinations.

Above it all, the heavens form layered spheres, stars embedded with mathematical clarity. Behind, Florence stands finished, its great dome already raised, though the scene is meant to predate it. Even the Latin inscription follows this logic: no embellishment, just reverence. Michelino didn’t illustrate the Comedy. He preserved its architecture.

Follow @historiaocculta

In Domenico di Michelino’s La Commedia illumina Firenze (1465), Dante is placed not in abstraction but in continuity—with Florence at his back and the full architecture of the afterlife before him. The Mount of Purgatory rises in tiers, but each level is active, not symbolic. At the base, a man is knighted by an angel—chosen through action, not birth. The ascent begins in struggle, shifts to urgency, and ends at a gate. Beyond it: Eden, not Heaven. A crowned man and woman wait in a walled garden.

To the left, another path breaks away. Here, figures lounge in comfort, but it doesn’t last. They are seized and pulled downward, funneled into Hell’s crowded tower. This descent is effortless—no climbing, no striving, only surrender. The structure is orderly. Each tier is populated. These aren’t loose ideas. They’re mapped destinations.

Above it all, the heavens form layered spheres, stars embedded with mathematical clarity. Behind, Florence stands finished, its great dome already raised, though the scene is meant to predate it. Even the Latin inscription follows this logic: no embellishment, just reverence. Michelino didn’t illustrate the Comedy. He preserved its architecture.

Follow @historiaocculta

17.05.202511:05

Marked With the Open Hand

The modern notion of a “blessing” has collapsed into sentiment: a polite phrase, a vague wish for good luck, or a sanctified pat on the back. But its roots are far older, tangled in law, lineage, and the spoken word’s binding force. In Old English, blēdsian meant to consecrate by marking with blood—often literal, as in animal sacrifice. A blessing was not kindly—it was covenantal. It invoked memory, place, and obligation.

In ancient Sumer, kings received blessings as transfers of cosmic legitimacy, their power tethered to the rhythms of celestial order. In the Torah, blessings split families and shaped nations: Jacob steals Esau’s with a touch and a lie, but once given, it cannot be revoked. The father’s words, spoken aloud, bind history more tightly than birthright. In these early texts, a blessing is not a reward; it is a declaration of fate, enforceable and irrevocable.

To bless someone was to recognize and declare their alignment with a pattern greater than themselves. It placed them within a structure—whether divine, dynastic, or juridical. The hand raised in blessing was not just a gesture of goodwill, but a sign of transmission, as if the speaker’s authority passed through the breath itself. Only much later, as legal authority unraveled and ancestral memory faded, did blessing become a loose synonym for favor or fortune. Its older forms remind us: blessing is not about feeling good. It is about being claimed.

Follow @historiaocculta

The modern notion of a “blessing” has collapsed into sentiment: a polite phrase, a vague wish for good luck, or a sanctified pat on the back. But its roots are far older, tangled in law, lineage, and the spoken word’s binding force. In Old English, blēdsian meant to consecrate by marking with blood—often literal, as in animal sacrifice. A blessing was not kindly—it was covenantal. It invoked memory, place, and obligation.

In ancient Sumer, kings received blessings as transfers of cosmic legitimacy, their power tethered to the rhythms of celestial order. In the Torah, blessings split families and shaped nations: Jacob steals Esau’s with a touch and a lie, but once given, it cannot be revoked. The father’s words, spoken aloud, bind history more tightly than birthright. In these early texts, a blessing is not a reward; it is a declaration of fate, enforceable and irrevocable.

To bless someone was to recognize and declare their alignment with a pattern greater than themselves. It placed them within a structure—whether divine, dynastic, or juridical. The hand raised in blessing was not just a gesture of goodwill, but a sign of transmission, as if the speaker’s authority passed through the breath itself. Only much later, as legal authority unraveled and ancestral memory faded, did blessing become a loose synonym for favor or fortune. Its older forms remind us: blessing is not about feeling good. It is about being claimed.

Follow @historiaocculta

16.05.202511:02

Sheet Light Through Iron Bones

When the Crystal Palace rose in Hyde Park in 1851, it wasn’t just its scale that staggered onlookers. Over 990,000 square feet of glass—machine-cut, near-identical, and shockingly smooth—had been fastened into a cathedral of iron. The Chance Brothers’ cylinder process, still in its infancy, had been pushed to industrial capacity, turning a fragile craft into scalable infrastructure.

This was no mere building. It was proof of concept for the machine age: that even light itself could be harnessed, standardized, and sold. And through that transparency came a message—raw ambition rendered visible. Visitors walking its endless aisles weren’t just seeing exhibits. They were walking inside a process that would soon transform cities, labor, and the atmosphere itself.

In its final home at Sydenham, the Palace housed one of the largest organs in the world—a towering instrument with over 4,500 pipes. Built not for worship, but for public spectacle, its music filled a space designed for scale and awe. Iron, glass, and sound: each disciplined by industrial force, yet orchestrated into something sublime.

Follow @historiaocculta

When the Crystal Palace rose in Hyde Park in 1851, it wasn’t just its scale that staggered onlookers. Over 990,000 square feet of glass—machine-cut, near-identical, and shockingly smooth—had been fastened into a cathedral of iron. The Chance Brothers’ cylinder process, still in its infancy, had been pushed to industrial capacity, turning a fragile craft into scalable infrastructure.

This was no mere building. It was proof of concept for the machine age: that even light itself could be harnessed, standardized, and sold. And through that transparency came a message—raw ambition rendered visible. Visitors walking its endless aisles weren’t just seeing exhibits. They were walking inside a process that would soon transform cities, labor, and the atmosphere itself.

In its final home at Sydenham, the Palace housed one of the largest organs in the world—a towering instrument with over 4,500 pipes. Built not for worship, but for public spectacle, its music filled a space designed for scale and awe. Iron, glass, and sound: each disciplined by industrial force, yet orchestrated into something sublime.

Follow @historiaocculta

15.05.202511:02

The Sounding Line Beyond Sunda

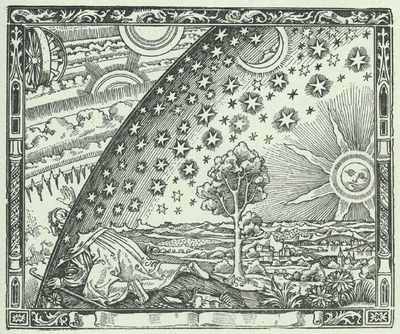

Lemuria did not begin as myth. In 1864, Philip Sclater noted a discontinuity in the distribution of lemur-like primates—found in Madagascar and parts of Asia, but absent from the regions in between. To explain this, he proposed a sunken landmass once linking those regions: Lemuria. This wasn’t fringe speculation. It was a formal scientific hypothesis made in an era before plate tectonics, when continental drift was still a forbidden idea.

The name outlasted the science. Lemuria was pulled into the orbit of Theosophy, where it became the cradle of an ancient human race—an evolutionary stage buried under oceans and obscured by time. From there it merged with older narratives. Tamil traditions spoke of Kumari Kandam, a lost land south of India swallowed by the sea. The stories did not match in purpose or tone, but the proximity was hard to ignore.

What complicates dismissal is what lies beneath the Indian Ocean. In the early 21st century, geologists identified continental fragments beneath layers of volcanic flow—now called Mauritia. No cities stood there, no culture left its mark. But the land was real, torn from Gondwana long before any story was written. Lemuria did not describe it. But it pointed in a direction science would later confirm, without knowing why.

Follow @historiaocculta

Lemuria did not begin as myth. In 1864, Philip Sclater noted a discontinuity in the distribution of lemur-like primates—found in Madagascar and parts of Asia, but absent from the regions in between. To explain this, he proposed a sunken landmass once linking those regions: Lemuria. This wasn’t fringe speculation. It was a formal scientific hypothesis made in an era before plate tectonics, when continental drift was still a forbidden idea.

The name outlasted the science. Lemuria was pulled into the orbit of Theosophy, where it became the cradle of an ancient human race—an evolutionary stage buried under oceans and obscured by time. From there it merged with older narratives. Tamil traditions spoke of Kumari Kandam, a lost land south of India swallowed by the sea. The stories did not match in purpose or tone, but the proximity was hard to ignore.

What complicates dismissal is what lies beneath the Indian Ocean. In the early 21st century, geologists identified continental fragments beneath layers of volcanic flow—now called Mauritia. No cities stood there, no culture left its mark. But the land was real, torn from Gondwana long before any story was written. Lemuria did not describe it. But it pointed in a direction science would later confirm, without knowing why.

Follow @historiaocculta

14.05.202511:03

Marked by the Step, Not the Door

A threshold is not a line between spaces—it is a mechanism for transformation. In the architecture of the ancient world, thresholds bore more weight than the walls themselves. They were loaded with ritual, embedded with protections, watched by gods. In Mesopotamia, inscriptions on door sills invoked Lamma, the guardian spirit, to prevent malevolent forces from crossing. In Egypt, the false door in tombs—cut into stone but leading nowhere—served as a conduit between the living and the dead, a passage only the ka could use.

The Latin word limen, source of “liminal,” originally referred to this architectural element. Not the idea of transition—but the physical place where the foot must rise, and fall, to move from one domain into another. Roman homes, especially patrician ones, marked their limina with apotropaic devices: phallic charms, inscribed spells, mosaics that stared back at intruders. Crossing was never casual. To step over a threshold was to subject oneself to scrutiny—by spirits, ancestors, or unseen legal orders. In temple design, thresholds could represent cosmic boundaries, mapped to the heavens. The temple’s entrance was not just a way in; it was a shift in alignment.

Early Christian churches preserved this logic. Holy water at the door was not just cleansing—it reset orientation. You passed into a different time. This is the ancient, practical root of the threshold—not symbolic in a modern, metaphorical sense, but engineered to act as a filter. To bar, to bless, to transform.

Follow @historiaocculta

A threshold is not a line between spaces—it is a mechanism for transformation. In the architecture of the ancient world, thresholds bore more weight than the walls themselves. They were loaded with ritual, embedded with protections, watched by gods. In Mesopotamia, inscriptions on door sills invoked Lamma, the guardian spirit, to prevent malevolent forces from crossing. In Egypt, the false door in tombs—cut into stone but leading nowhere—served as a conduit between the living and the dead, a passage only the ka could use.

The Latin word limen, source of “liminal,” originally referred to this architectural element. Not the idea of transition—but the physical place where the foot must rise, and fall, to move from one domain into another. Roman homes, especially patrician ones, marked their limina with apotropaic devices: phallic charms, inscribed spells, mosaics that stared back at intruders. Crossing was never casual. To step over a threshold was to subject oneself to scrutiny—by spirits, ancestors, or unseen legal orders. In temple design, thresholds could represent cosmic boundaries, mapped to the heavens. The temple’s entrance was not just a way in; it was a shift in alignment.

Early Christian churches preserved this logic. Holy water at the door was not just cleansing—it reset orientation. You passed into a different time. This is the ancient, practical root of the threshold—not symbolic in a modern, metaphorical sense, but engineered to act as a filter. To bar, to bless, to transform.

Follow @historiaocculta

13.05.202511:02

The Hidden Charge in Red Brick

Red brick wasn’t just common—it was foundational. For centuries, it formed the bones of factories, cathedrals, train stations, and entire city blocks. Even now, beneath modern facades, many buildings still carry their original brickwork, sealed behind plaster or stone cladding. The pattern repeats across continents—uniform size, deep red color, often blackened as if heat-touched.

But beyond structure, red brick carries a property less discussed: conductivity. Fired clay mixed with iron-rich minerals can hold and pass electric charge. It doesn’t spark like metal, but under the right conditions, it stores voltage—acting almost like a capacitor. Modern research has confirmed this. The same material once used for strength and heat resistance also responds to current.

It raises questions—not about what brick is, but why it was chosen, replicated, and embedded in so much of the built world. And whether it was serving more than one purpose all along.

Follow @historiaocculta

Red brick wasn’t just common—it was foundational. For centuries, it formed the bones of factories, cathedrals, train stations, and entire city blocks. Even now, beneath modern facades, many buildings still carry their original brickwork, sealed behind plaster or stone cladding. The pattern repeats across continents—uniform size, deep red color, often blackened as if heat-touched.

But beyond structure, red brick carries a property less discussed: conductivity. Fired clay mixed with iron-rich minerals can hold and pass electric charge. It doesn’t spark like metal, but under the right conditions, it stores voltage—acting almost like a capacitor. Modern research has confirmed this. The same material once used for strength and heat resistance also responds to current.

It raises questions—not about what brick is, but why it was chosen, replicated, and embedded in so much of the built world. And whether it was serving more than one purpose all along.

Follow @historiaocculta

12.05.202511:01

Ginnungagap and the Weight of First Blood

Before the world existed, there was only the void—Ginnungagap—flanked by fire in the south (Muspelheim) and ice in the north (Niflheim). Where these extremes collided, drops of meltwater gathered and quickened, giving rise to Ymir, the primal giant, and Audhumla, the great cow whose milk sustained him.

As Audhumla licked the salty ice, she uncovered Buri, ancestor of the gods. From Ymir’s own body came a brood of giants, but creation demanded sacrifice. Odin and his brothers, sons of Buri’s line, slew Ymir and fashioned the world from his remains: flesh became earth, blood the seas, bones the mountains, teeth the stones, and skull the sky. His scattered brains drifted as clouds.

The Norse cosmos did not emerge whole. It was hacked, hewn, and pieced together. Its origin is not serene or absolute but a memory of something raw and brutal, where order is not the opposite of chaos but its hardened offspring.

Follow @historiaocculta

Before the world existed, there was only the void—Ginnungagap—flanked by fire in the south (Muspelheim) and ice in the north (Niflheim). Where these extremes collided, drops of meltwater gathered and quickened, giving rise to Ymir, the primal giant, and Audhumla, the great cow whose milk sustained him.

As Audhumla licked the salty ice, she uncovered Buri, ancestor of the gods. From Ymir’s own body came a brood of giants, but creation demanded sacrifice. Odin and his brothers, sons of Buri’s line, slew Ymir and fashioned the world from his remains: flesh became earth, blood the seas, bones the mountains, teeth the stones, and skull the sky. His scattered brains drifted as clouds.

The Norse cosmos did not emerge whole. It was hacked, hewn, and pieced together. Its origin is not serene or absolute but a memory of something raw and brutal, where order is not the opposite of chaos but its hardened offspring.

Follow @historiaocculta

11.05.202511:02

Flesh Set Against Forgetting

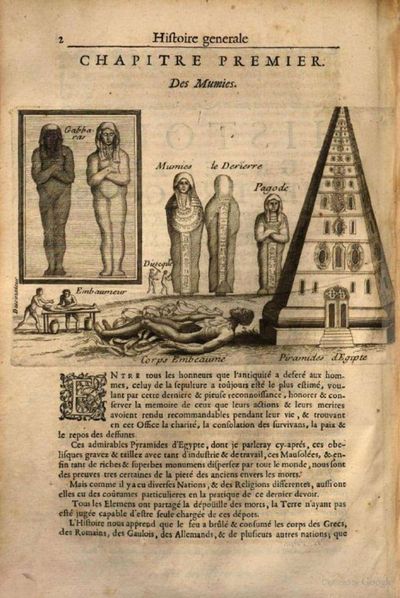

When a society turns to embalming, it speaks of a deeper refusal to surrender the body to time’s silence. The dead are not merely honored—they are made permanent, preserved as witnesses to a life that memory alone cannot hold.

In ancient Egypt, to embalm was to ensure the spirit’s ability to recognize itself in eternity, a tether between seen and unseen worlds. In Victorian Britain, embalming surged in popularity as families, shaken by industrialization and mass death, sought to slow the final departure of their loved ones. Even in modern times, the practice reflects a complicated relationship with death: a denial of decay, a tribute to individuality, and a belief—whether religious, cultural, or psychological—that the body retains meaning long after the breath has left it.

To embalm is to insist that the past remain visibly present. It reveals a civilization’s fear of oblivion—and its faith that memory must be more than dust.

Follow @historiaocculta

When a society turns to embalming, it speaks of a deeper refusal to surrender the body to time’s silence. The dead are not merely honored—they are made permanent, preserved as witnesses to a life that memory alone cannot hold.

In ancient Egypt, to embalm was to ensure the spirit’s ability to recognize itself in eternity, a tether between seen and unseen worlds. In Victorian Britain, embalming surged in popularity as families, shaken by industrialization and mass death, sought to slow the final departure of their loved ones. Even in modern times, the practice reflects a complicated relationship with death: a denial of decay, a tribute to individuality, and a belief—whether religious, cultural, or psychological—that the body retains meaning long after the breath has left it.

To embalm is to insist that the past remain visibly present. It reveals a civilization’s fear of oblivion—and its faith that memory must be more than dust.

Follow @historiaocculta

10.05.202511:05

The Cities That Appeared, and Then Disappeared

From 1851 to the early 20th century, World’s fairs rose in cities across the realm—massive expos said to showcase progress, invention, and civilization. But what they revealed looked less like innovation and more like memory: vast classical structures, domes, arches, columned halls stretching for acres. The 1893 Chicago Exposition alone covered over 600 acres with more than 200 monumental buildings—built, they said, in under two years.

Official accounts claimed the architecture was temporary, made from plaster and wood. But photographs tell another story. Stone-like finishes, detailed interiors, immense scale, and design far beyond what transitory construction should allow. People came to marvel, but also to be taught—to receive the official version of history, of invention, of what was new.

And when it ended, nearly all of it was demolished. Buried, burned, or erased. What’s left behind suggests these fairs weren’t simply built to celebrate the future—but to rewrite the past.

Follow @historiaocculta

From 1851 to the early 20th century, World’s fairs rose in cities across the realm—massive expos said to showcase progress, invention, and civilization. But what they revealed looked less like innovation and more like memory: vast classical structures, domes, arches, columned halls stretching for acres. The 1893 Chicago Exposition alone covered over 600 acres with more than 200 monumental buildings—built, they said, in under two years.

Official accounts claimed the architecture was temporary, made from plaster and wood. But photographs tell another story. Stone-like finishes, detailed interiors, immense scale, and design far beyond what transitory construction should allow. People came to marvel, but also to be taught—to receive the official version of history, of invention, of what was new.

And when it ended, nearly all of it was demolished. Buried, burned, or erased. What’s left behind suggests these fairs weren’t simply built to celebrate the future—but to rewrite the past.

Follow @historiaocculta

09.05.202511:04

Every Cell an Altar, Every Nerve a Pilgrimage

There is a theory that reverses the usual direction of salvation. Instead of reaching outward—toward heaven, toward a distant God—it folds the entire drama of redemption inward, into the human body itself. Here, the sacred word is not just spoken or written; it is seeded into matter, a biological script waiting to be enacted.

At the heart of this vision is a hidden process: a seed of potential, descending from the brain through the spinal column, cycling in rhythm with the lunar calendar. This seed—the so-called “Christ within”—must be nurtured, protected from dissipation, and eventually raised again. The ancient narrative of crucifixion and resurrection becomes, in this view, not symbolic of external events but a real physiological transfiguration. The death of the seed through bodily excess mirrors the crucifixion; its rise through conscious discipline is the resurrection.

This idea blurs all lines between spirit and flesh, doctrine and anatomy. Salvation is no longer a promise made to the soul alone but a precise alchemy of body and mind. The path to awakening becomes a literal pilgrimage within: the spine a sacred road, the fluids and forces of the body the true sacraments.

Follow @historiaocculta

There is a theory that reverses the usual direction of salvation. Instead of reaching outward—toward heaven, toward a distant God—it folds the entire drama of redemption inward, into the human body itself. Here, the sacred word is not just spoken or written; it is seeded into matter, a biological script waiting to be enacted.

At the heart of this vision is a hidden process: a seed of potential, descending from the brain through the spinal column, cycling in rhythm with the lunar calendar. This seed—the so-called “Christ within”—must be nurtured, protected from dissipation, and eventually raised again. The ancient narrative of crucifixion and resurrection becomes, in this view, not symbolic of external events but a real physiological transfiguration. The death of the seed through bodily excess mirrors the crucifixion; its rise through conscious discipline is the resurrection.

This idea blurs all lines between spirit and flesh, doctrine and anatomy. Salvation is no longer a promise made to the soul alone but a precise alchemy of body and mind. The path to awakening becomes a literal pilgrimage within: the spine a sacred road, the fluids and forces of the body the true sacraments.

Follow @historiaocculta

08.05.202511:04

The Winged Remnants of Our Own Design

For thousands of years, pigeons have fluttered at the margins of human intention—never fully wild, never entirely controlled. Domesticated by 3000 BCE in Mesopotamia, rock doves became fixtures of early cities, their homing instinct harnessed from the ancient Near East through Rome’s military networks. Even in World War I, pigeons carried critical messages across collapsing front lines, their reliability outlasting successive revolutions in warfare.

Beyond these official roles, they shaped survival in quieter ways. Medieval dovecotes—stone towers for nesting—sustained rural protein supplies and fed industries reliant on their nitrate-rich droppings. In 19th-century Paris, pigeon-keeping crossed class lines, turning rooftops into shared aviaries, where utility and companionship blurred.

Unlike the omens tied to owls or crows, pigeons occupy a softer threshold. Some folk beliefs—especially in urban settings—hold that their low, rolling coos can mark thin moments between worlds, brief signs of unseen currents brushing against the living. Whether or not such meanings hold, pigeons remain permanent exiles of our own making, too bound to us to ever truly vanish.

Follow @historiaocculta

For thousands of years, pigeons have fluttered at the margins of human intention—never fully wild, never entirely controlled. Domesticated by 3000 BCE in Mesopotamia, rock doves became fixtures of early cities, their homing instinct harnessed from the ancient Near East through Rome’s military networks. Even in World War I, pigeons carried critical messages across collapsing front lines, their reliability outlasting successive revolutions in warfare.

Beyond these official roles, they shaped survival in quieter ways. Medieval dovecotes—stone towers for nesting—sustained rural protein supplies and fed industries reliant on their nitrate-rich droppings. In 19th-century Paris, pigeon-keeping crossed class lines, turning rooftops into shared aviaries, where utility and companionship blurred.

Unlike the omens tied to owls or crows, pigeons occupy a softer threshold. Some folk beliefs—especially in urban settings—hold that their low, rolling coos can mark thin moments between worlds, brief signs of unseen currents brushing against the living. Whether or not such meanings hold, pigeons remain permanent exiles of our own making, too bound to us to ever truly vanish.

Follow @historiaocculta

07.05.202511:04

The Land Beyond the North Wind

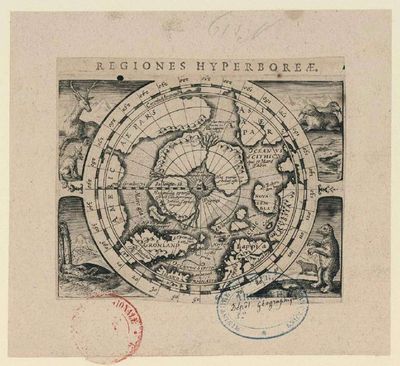

In the oldest Greek accounts, Hyperborea lay far to the north—beyond Boreas, the god of the northern wind. It was said to be a place of long light, rich soil, and great stillness. Herodotus called it a mystery. Pindar wrote that its people never aged. Hecataeus placed it near the source of the world’s great rivers. None claimed to have seen it. But all spoke of it as if it had once been real.

Descriptions were consistent: a circular land, high mountains, temperate air, and a rhythm untouched by war or decay. Apollo was said to journey there each year and return renewed. It wasn’t imagined as heaven. It was remembered as origin.

For centuries, mapmakers included it—often near the Arctic, sometimes split into four by rivers flowing from a central mount. Then, gradually, it vanished. The names changed. The outlines faded. And what was once marked became myth.

Follow @historiaocculta

In the oldest Greek accounts, Hyperborea lay far to the north—beyond Boreas, the god of the northern wind. It was said to be a place of long light, rich soil, and great stillness. Herodotus called it a mystery. Pindar wrote that its people never aged. Hecataeus placed it near the source of the world’s great rivers. None claimed to have seen it. But all spoke of it as if it had once been real.

Descriptions were consistent: a circular land, high mountains, temperate air, and a rhythm untouched by war or decay. Apollo was said to journey there each year and return renewed. It wasn’t imagined as heaven. It was remembered as origin.

For centuries, mapmakers included it—often near the Arctic, sometimes split into four by rivers flowing from a central mount. Then, gradually, it vanished. The names changed. The outlines faded. And what was once marked became myth.

Follow @historiaocculta

06.05.202511:02

The Unquiet Dead of Purgatory Registers

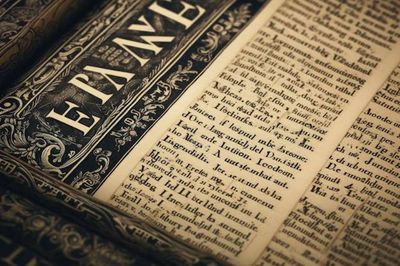

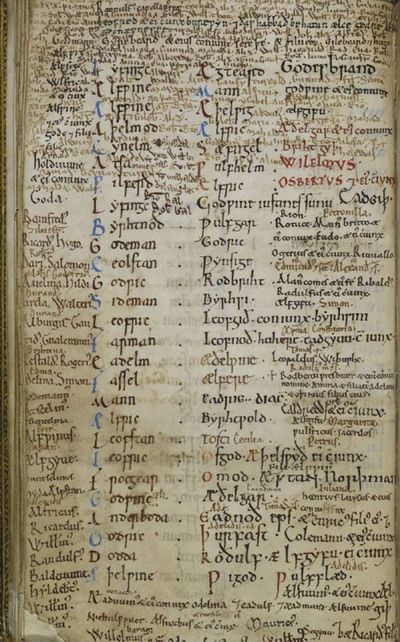

In medieval Europe, death was not the end of obligation. Across the Catholic world, monasteries kept purgatory registers (libri purgatorii)—thick volumes listing the names of the dead whose families paid for prayers to ease their passage through the afterlife. These books turned remembrance into a system: each name a contract, binding monks to recite masses long after the mourner was gone.

The sheer scale is startling. At Cluny Abbey, one of the largest, registers stretched into tens of thousands of entries, recording not saints or nobles, but the everyday dead—blacksmiths, widows, children. Many appear nowhere else in history. Through these lists, the forgotten were kept in circulation, their souls woven into daily monastic ritual. For the monks, speaking a dead person’s name was an act of precision as much as faith: every soul had a place in the ledger, and every ledger was a form of spiritual infrastructure.

Fragments of these registers survive today, scattered in archives. They are not dramatic to read—just names, dates, and payments. But in their accumulation, they show something stark: a medieval world where the dead remained active participants in the economy and in memory, and where forgetting was a risk that had to be managed—line by line.

Follow @historiaocculta

In medieval Europe, death was not the end of obligation. Across the Catholic world, monasteries kept purgatory registers (libri purgatorii)—thick volumes listing the names of the dead whose families paid for prayers to ease their passage through the afterlife. These books turned remembrance into a system: each name a contract, binding monks to recite masses long after the mourner was gone.

The sheer scale is startling. At Cluny Abbey, one of the largest, registers stretched into tens of thousands of entries, recording not saints or nobles, but the everyday dead—blacksmiths, widows, children. Many appear nowhere else in history. Through these lists, the forgotten were kept in circulation, their souls woven into daily monastic ritual. For the monks, speaking a dead person’s name was an act of precision as much as faith: every soul had a place in the ledger, and every ledger was a form of spiritual infrastructure.

Fragments of these registers survive today, scattered in archives. They are not dramatic to read—just names, dates, and payments. But in their accumulation, they show something stark: a medieval world where the dead remained active participants in the economy and in memory, and where forgetting was a risk that had to be managed—line by line.

Follow @historiaocculta

05.05.202511:01

The Organ That Played with Water

Long before electricity, before valves and wires, Ktesibios built an instrument that used water to shape sound. In 3rd century BCE Alexandria, he designed the first known hydraulic organ—not as a curiosity, but as a working machine of pressure, balance, and tone.

Water sat beneath a closed chamber, its weight forcing air upward through pipes as it rose. A system of keys controlled the flow, allowing the player to shape notes with precision. It was called the hydraulis, and it worked not in theory but in practice—loud enough to fill open air, stable enough to hold pitch. Later versions were used in Roman arenas and Byzantine courts, but it began with a single insight: that sound could be stabilized by water.

Ktesibios wasn’t building music for pleasure alone. He was tracing the boundary between force and form. What he left behind wasn’t just the first organ—it was one of the earliest machines designed to give structure to breath.

Follow @historiaocculta

Long before electricity, before valves and wires, Ktesibios built an instrument that used water to shape sound. In 3rd century BCE Alexandria, he designed the first known hydraulic organ—not as a curiosity, but as a working machine of pressure, balance, and tone.

Water sat beneath a closed chamber, its weight forcing air upward through pipes as it rose. A system of keys controlled the flow, allowing the player to shape notes with precision. It was called the hydraulis, and it worked not in theory but in practice—loud enough to fill open air, stable enough to hold pitch. Later versions were used in Roman arenas and Byzantine courts, but it began with a single insight: that sound could be stabilized by water.

Ktesibios wasn’t building music for pleasure alone. He was tracing the boundary between force and form. What he left behind wasn’t just the first organ—it was one of the earliest machines designed to give structure to breath.

Follow @historiaocculta

Records

19.05.202523:59

1.6KSubscribers29.03.202501:08

1100Citation index15.04.202517:04

16.9KAverage views per post15.04.202523:34

16.9KAverage views per ad post06.04.202514:00

24.49%ER02.04.202523:59

4537.10%ERRGrowth

Subscribers

Citation index

Avg views per post

Avg views per ad post

ER

ERR

Log in to unlock more functionality.